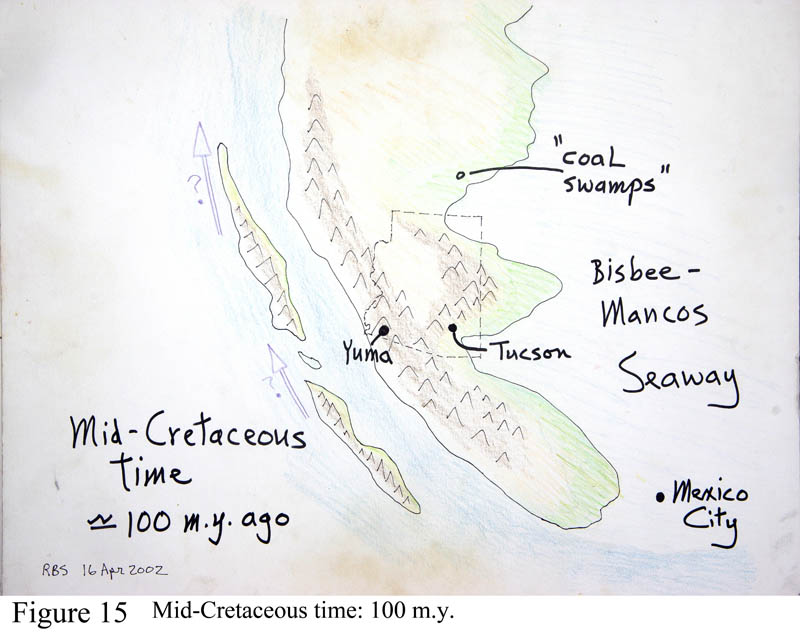

Arizona, mid-Cretaceous

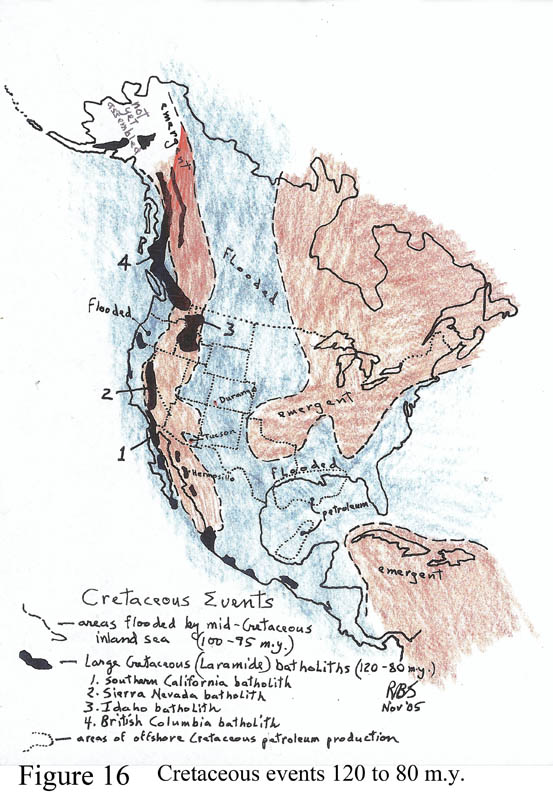

Figures 15 and 16. Arizona in mid-Cretaceous time. About 100 m.y. ago, the central portion of North America sank below sea level and was flooded by a shallow seaway that stretched from basically Tucson eastward to the Appalachians, the entire mid-continent from Texas to the Arctic Ocean became flooded. And as well California was evolving, while much it was also covered by shallow parts of the encroaching Pacific Ocean - resembling Japan and the Sea of Japan off mainland Asia. Beds deposited under the 'Bisbee-Mancos' Sea are locally called the Bisbee Group, named for their great exposures in the Mule Mountains heading east on highway 80 from Bisbee towards Douglas. The west coast of this seaway became lined with lowland forests and swamps that eventually decayed into vast lignite coal beds - labeled 'coal swamps' on the figure. These will eventually fuel all the western region coal-fired electric power plants. Arizona's significant coal deposit is atop Black Mesa. The far western edge of this sea extended as far west as Kitt Peak - long before the modern mountain existed. Figure 15 shows the extent of flooding across the continent. Note the very altered setting in Central America and the Caribbean. Flying over the region, you could not pick out the site of future Tucson.

The ultimate reason for this buckling down of the continent in its mid-section appears to be due to the intrusion along the west coast region of a huge amount of granites underground as the process of seafloor spreading and subduction speeded up greatly. So the west coast region was shoved up and the mid-continent sank. The west coast batholiths are a sight to behold, as noted below.

The trademark deposits of the Cretaceous marine beds in the four corners region are thick beds of gray-colored muds containing many coal beds, then capped by cliffs of hard yellow sandstone that contains petrified wood and dino fossils. The beds are present in our region but not along popular highways. The series is present on the Apache Reservation near Winkelman, and along the highway up Black Mesa, off the connecting highway between Tuba City and Kayenta. Most spectacular places to view the beds are in the hills above Mancos and Durango, Colorado, and especially on the road up into Mesa Verde National Park west of Durango, or along the Highway 9 eastern approach into Zion National Park. At both the Zion and Mesa Verde locations, the highways have been damaged and warped by landslides that develop in the soft Cretaceous gray mud beds called the Mancos Shale. In those areas you can find cemented beds of oysters, which made the Mesozoic 'reef' deposits, at a time before modern corals engaged in the process of reef-building. There is even a thin oyster reef visible in the Tucson Mountains, along the Yetman trail a half-mile south of the Gates Pass road (west Speedway Blvd).

While the mid-continent was flooding to the east, along the old west coast a positively amazing magmatic event was occurring. A tremendous thick and massive series of granite batholiths were rising and cooling in the upper crust all along the west coast region from Mexico to nearly Alaska in the time frame 120-80 m.y. ago. (The sea flooded the mid-continent at 100-90 m.y. ago.) A batholith is defined as a mass of granite with more than 100 square miles of modern surface exposure. These are shown in Figures 13, 14, and 16, labeled 'Cretaceous batholiths.' They include the modern Sierra Nevadas of California (Figure 52) and the Southern California batholith that extends well into Baja. To the north lays the Idaho batholith, and the gargantuan British Columbia batholith.

The 'high Sierras' country of eastern California is popular with tourists, skiers, botanists and geologists, containing Sequoia, Kings Canyon, and Yosemite National Parks. This single batholithic mass is 75 miles wide, 450 miles long and some 10 miles thick, with a volume of at least 350,000 cubic miles - and all granite! The tallest mountain in the US outside Alaska is Mt. Whitney, 14,496 ft, in the central part of the Sierras just west of the tiny berg of Lone Pine, my birth place.

The best route to sense the magnitude of the batholith problem is to enjoy the granite walls at Yosemite (ignoring the gawking crowds), and the world's tallest sheer granite cliff called El Capitan, often with bold climbers clinging to it; then travel highway 41/120 from Yosemite Park east over the top of the range at Tuolumne Meadows and Tioga Pass, then down the east side to Lee Vining and Mono Lake. Along the last part of the traverse over the Sierran crest, you can spot very dark-colored rock masses in the canyons, which represent older Paleozoic shales which were caught up within the rising granite masses and thoroughly pressure-cooked. These masses of older rock caught up within the rising magmas of the batholith are called 'roof pendants.'

As the granites were rising and mushrooming outward - remember the 60s lava lamps? - above them a bunch of volcanoes were erupting. Later the entire long linear Sierra Nevada massif was literally tilted downwards to the west, so that the remnant volcanic capping series are found on the western flank. This series of rhyolites and andesites happens to have changed the entire course of humanity on Earth--because these rocks are the 'mother lode' of California's gold deposits that came to define U.S. political history since December 1848 when James Marshall made the first accidental strike at Sutter's Mill on the American River. (Check out the site, along highway 49 between Placerville and Auburn, nearly due east of Sacramento.) I have waded in the water at that place, where now sits a tourist center, my head spinning with history. That event opened the West like nothing else, featuring the good, the bad and the ugly, and reset the course of U.S. political ambitions towards it new economic empire that now blossoms. To visit this country, merely travel Highway 49, the gold rush highway. Sutter's Fort State Historic Park sits in downtown Sacramento and reviews that history. Most miners went broke, while saloon-keepers, freight companies and dance hall girls did fine.

The line of batholiths is such a strong geologic barrier that it now forms the western edge of our .

Why this amazing event of granite formation, which has no equal in the region? The magmas melted deeply along the subduction zone just to the west (before coastal California existed) and rose through the crust. But the rate of closure or collision between North America and Pacifica became much more rapid at 120-80 m.y. ago and so there was much more frictional heating at the subduction zone and more rapid rate of melting. Something profound happened inside the Earth to cause this, evidenced by the fact that during this time - 120 to 80 m.y. ago - the Earth cancelled its normal routine of rapid magnetic pole shifts and became stuck into 'normal' polarity. I have no idea how this happened, but it coincides EXACTLY with the time of formation of the giant batholiths along the west coast. Probably the spreading center in the Pacific Ocean quickened its rate of spreading, causing extra high-speed subduction and extra granite production. This caused the entire continent to buckle up along the west coast, and down in its mid-part, causing the flooding and sedimentation of the Cretaceous seabeds.